Published on 06.01.2017 in [residencies]

Because of the amount of audio files, this post is best experienced using Firefox!

Quiet Music, Weak Sounds

Introduction

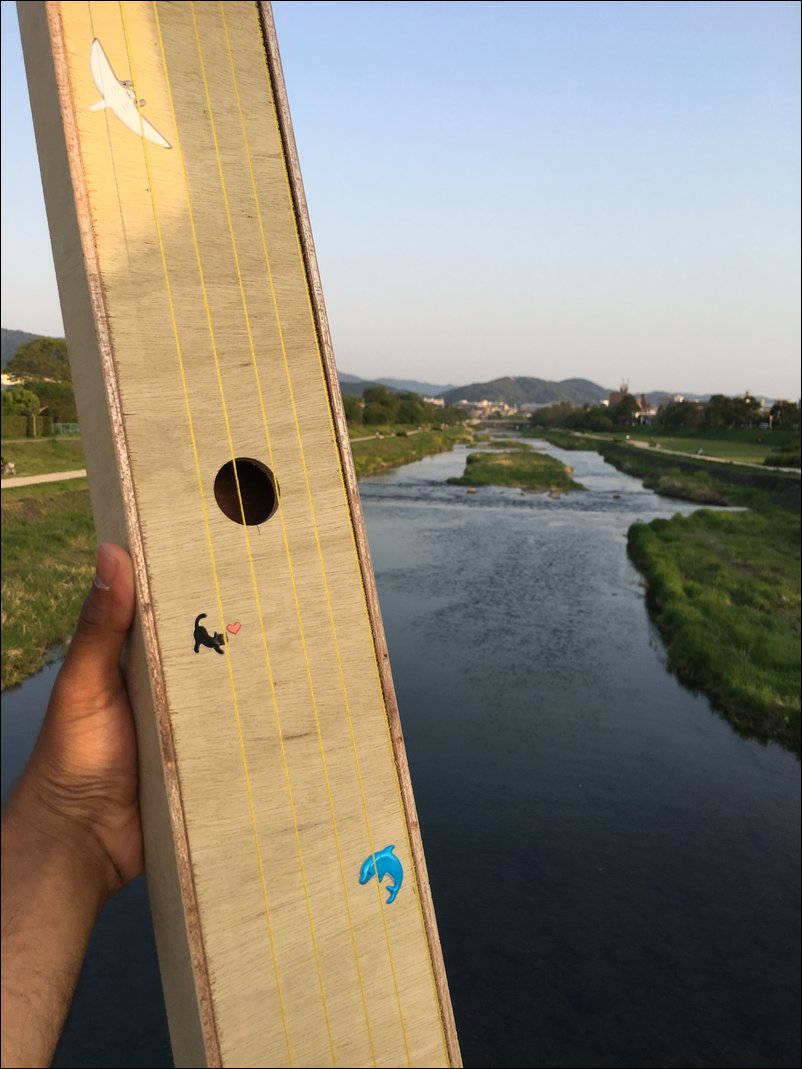

Early one summer morning in Kyoto, I took this photo on along the banks of the Kamo River.

On the left bank, a women greeted the morning with outstretched arms. Up above, three birds circled over the water. Kyoto, already a sleepy city, was still waking up. In its stillness, all I had was the quiet of the city's early dawn around me. From that vantage point, Kyoto's deep morning silence stretched far into the horizon, up the Kamo River valley, and into the mountains hidden behind the clouds.

Since that summer in 2012 I have been searching for quiet sounds all around me. Sometimes these are literally quiet sounds — inaudible because of their low volume compared to the bigger, louder sounds around them. But often times these quiet sounds are not so quiet at all, and instead are quiet because of our relationship to them. They are sounds that we don't pay attention to. They take up less space. They are often "overheard" (analogous to "overlooked") because they are not usually sounds we focus on. They are effectively inaudible, used here in a similar way one might use the term "invisible". They are muted and minuscule, diminutive and shrunken, minor and pathetic. They have no wants and cause no trouble. They are sounds pushed off to the side and forgotten, overshadowed by the larger, familiar and more heroic sounds in the environment that people instantly recognize, are drawn towards, and quickly reference when describing a place.

Some examples of quiet sounds that I've come across include:

The reverberations of street life transduced through a hollow pole

The piercing pitching of neon signs

The rhythmic knocking inside of cross-walk buttons

The brushing of ripples against a lake's shore

The soft patterings of light February snow

Most of my work for the past five years has been shifting people's attention to those sounds, in an attempt to broaden our understanding of the world around us. Through this deeper understanding, we can create new, original, and more personal relationships to our environment through the discovery of the delicate, poetic, and ephemeral sounds around us — if only we took the time to listen.

My time in Japan, especially as an InterLab Researcher at YCAM, taught me a lot about listening in new ways, and I knew I would one day return back to Kyoto to get to deeply know the city and the sounds within.

The following year, I contacted Tetsuya Umeda, a sound artist from the Kansai area, about the possibility of doing listening tours in Kyoto to explore its sounds, and he advised me to get in touch with Social Kitchen, a community arts center in the city.

It would take a couple of years before I could find a way to work with Social Kitchen, and in 2015 I was introduced to the Asian Cultural Council, who ended up supporting my time in Kyoto through a fellowship grant.

I got in touch with Social Kitchen again in 2016, and they introduced me to Eisuke Yanagisawa as someone with whom I should collaborate with during my time in Kyoto.

Five years after I took that photo on the Kamo River, I was able to return to Kyoto and embark on a four-week long residency to explore its sounds through a series of workshops and field work research expeditions, titled Quiet Music, Weak Sounds

Before I arrived, Social Kitchen, Eisuke and I came up with the following program:

Quiet Music, Weak Sounds is a collaboration between sound artists Johann Diedrick and Eisuke Yanagisawa to discover, amplify, and share the subtle sounds in Kyoto, Japan.

Over the course of four weeks, Diedrick and Yanagisawa will explore Kyoto’s soundscape with custom microphones, amplifiers and field recorders.

Informed by their findings, the two will host a series of workshops, teaching members of the community how to build and use their own sonic investigation tools.

They will turn participants into acoustic explorers and take them on explorations of Kyoto to find, record, edit, and present their own found sounds.

Afterward they will construct Aeolian harps with the participants and introduce the harp's sounds to Kyoto’s Kamo River path.

Finally, the two will present their findings to the community at large, in the form of a talk and reception party.

After finally arriving in Kyoto in April 2017, Eisuke and I met and began our collaboration together.

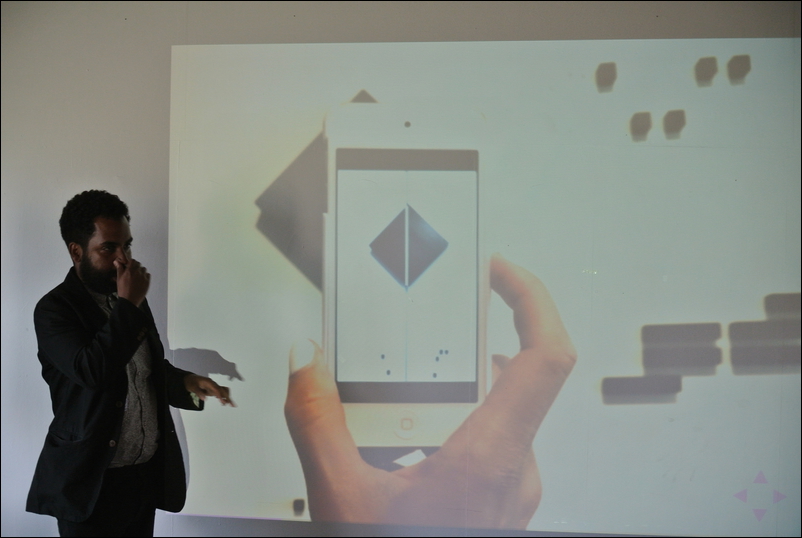

Mobile Listening Kit Workshop

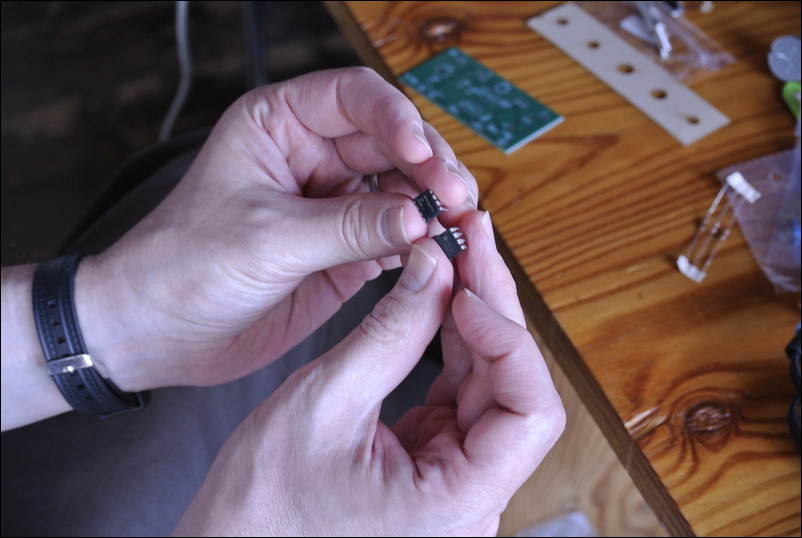

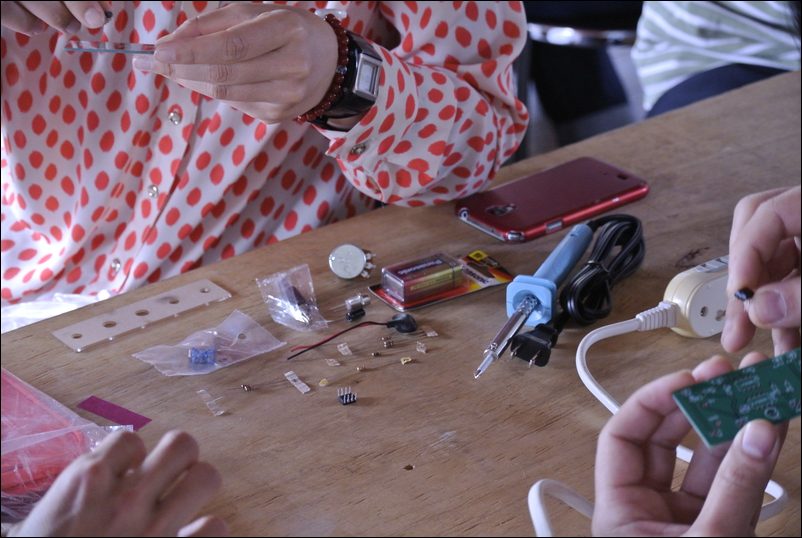

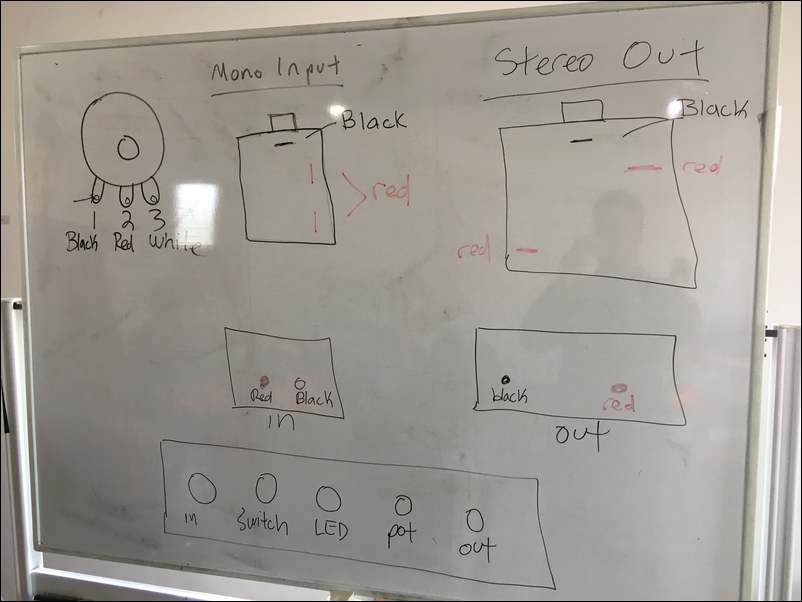

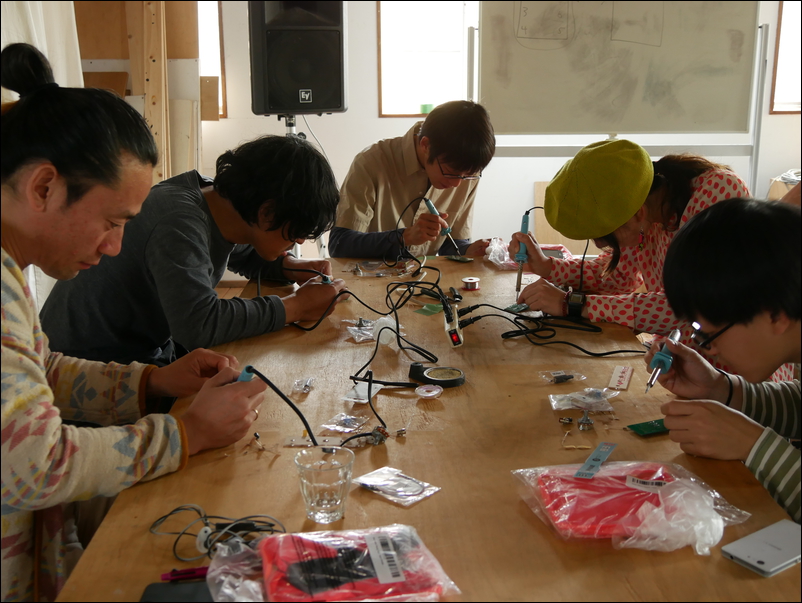

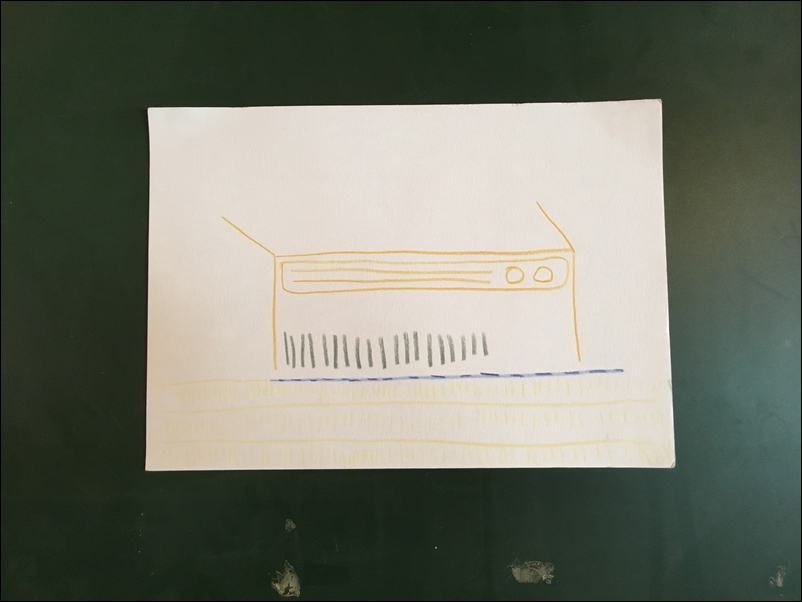

The first event hosted at Social Kitchen was a Mobile Listening Kit workshop. The workshop introduced participants to the world of sound art and provided techniques for making tools to create these experiences. This included the fabrication of a mobile listening kit and a contact microphone for use in installations, performances, and scientific research.

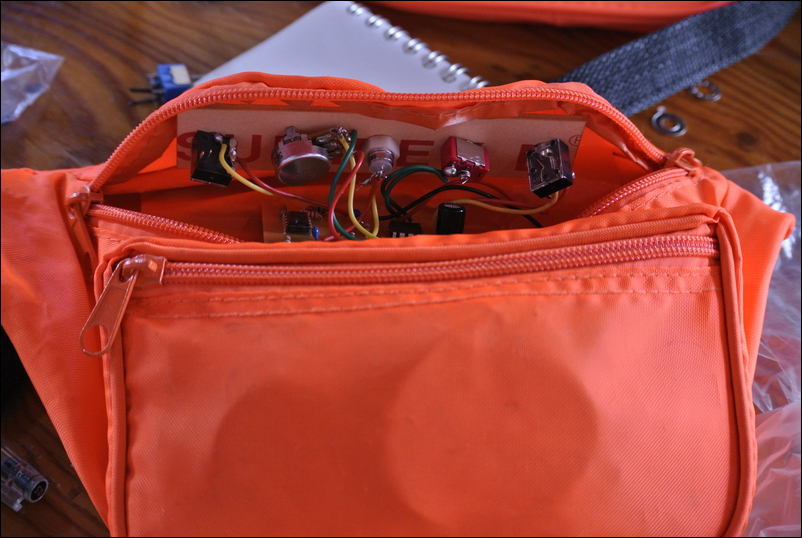

The mobile listening kits are portable amplifiers that can be used to hear quiet sounds in your environment. They consist of an input for different kinds of microphones — in the workshop we built and used contact microphones. You can adjust the volume of the input sound with a volume knob, and hear vibrations on surfaces through headphones or speakers. The kits are used to focus in on sounds that normally can't be heard because of their volume, and are designed to be portable for everyday use and exploration.

Most of the participants had never built any kind of electronic device before, and the workshop involved a lot of soldering and hands-on fabrication. It was important for me to have people actually build these kits, instead of using pre-built ones, because I think it is important to teach people how to teach themselves. Only by learning how to teach myself was I able to do and make the things I can today. I think it is critically important for artists to learn how their tools work and function, so that they can modify them for their own creative purposes.

Field Recording Workshop

The next day, Eisuke and I hosted a field recording workshop. In this workshop we gave participants the opportunity to find and record sounds outside with their mobile listening kits, field recorders, and different kinds of microphones. We didn't give much instruction on what to listen for, except only to try to discover sounds in places where they least expected. In this way, the workshop encouraged listeners to reimagine their sonic environment by playfully exploring the world through their ears.

The workshop began with a quick lecture on how to use microphones and field recorders for recording sound.

Soon after we went to Goryou Shrine, a Shinto shrine just a short walk from Social Kitchen. We spent most of the afternoon at the shrine exploring its cracks, surfaces, and hidden spaces.

After spending two hours recording sounds, we came back and did a short lecture on editing field recordings. At the end of the workshop, participants presented their recordings to each other, which prompted lively questions and discussion.

Aeolian Harp Workshop

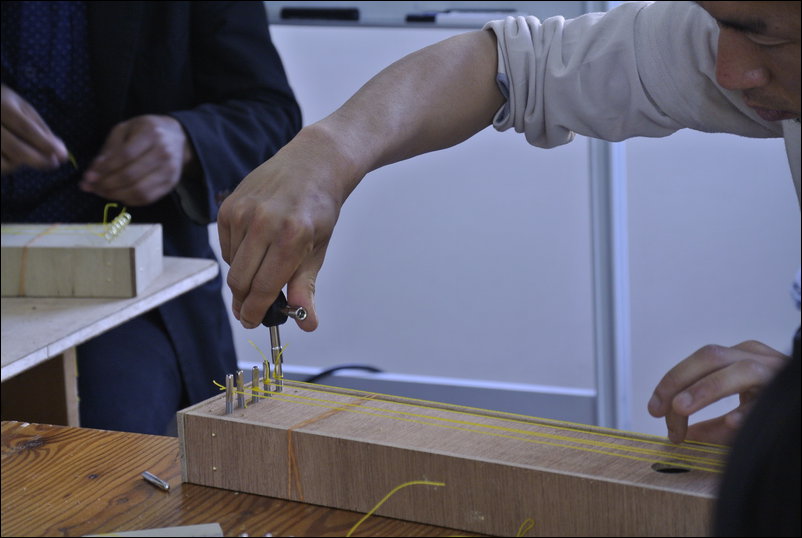

In the final workshop, we built Aeolian harps, a type of string instrument played by the wind.

Aeolian harps are objects of mystique because of the quality of the sound they produce and how that sound is made. They can range in look and form, but in general they look like simplified harps or guitars, with a hollow wooden body, usually with a sound hole, and a number of strings stretched across. Instead of plucking or bowing the harp, you can place it in the vicinity of a moderate, consistent gust of wind, and as the wind vibrates the strings, the harp produces a ghostly, haunting sound — seemingly out of thin air.

We were both really excited to host the workshop because we knew it would be a beautiful demonstration of how one can collaborate with the environment to produce sound, instead of treating sounds in the environment as a resource to be extracted as we had done in the two previous workshops. We knew that producing sounds from the harp would be difficult for a number of reasons, least of which would be that we didn't have any control of the wind on the day of the workshop. Conceptually this worked in our favor, because it meant that participants had to concentrate hard to produce and hear the sounds from the harp. They wouldn't be able to get the immediate satisfaction of making sounds like you would with an electric guitar, drum set, or computer. Instead, they had to be very patient and work with the environment to orient the harp in such a way that when a gust of wind blew their way, the harp would sound. Each sound was to be precious. The participants had to wait in anticipation, excitement, and yes, frustration, for each sound to come. Our hope was for them to ultimately develop a new kind of appreciation for weak, quiet sounds that can be just as fleeting as the wind.

Before starting this workshop, Eisuke and I traveled to Osaka to visit Kosuke Nakagawa, an expert at building string instruments including Aeolian harps. At his studio he showed us his instruments and walked us through how to build an Aeolian harp for our workshop.

Here is a video of our prototype in action:

Back at Social Kitchen, we built our Aeolian harps together.

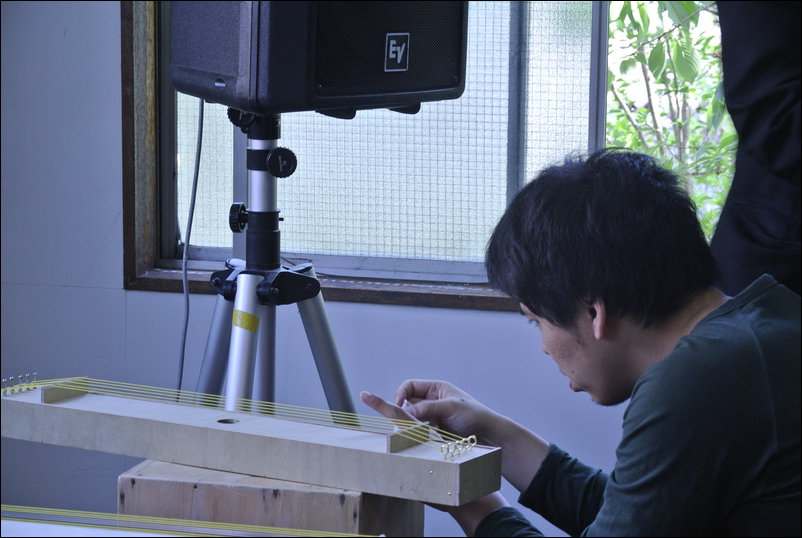

When we were done, we brought their natural singing sound to the Kamo River. As expected, it was difficult to get the harps to sing. Walking around the river, we searched for the best place to find ideal wind conditions. Participants readjusted and realigned their harps in order to find the best position. In the process, they developed a consciousness around wind speed, path, and direction in the surrounding environment. And soon enough, the sounds came.

You can hear a sample of what the Aeolian harp sounded like here:

Field Work

During my last week in Kyoto, Eisuke and I were able to spend two days doing our own field work. We were both interested in quiet sounds, but from two different perspectives. I was interested in sounds that were quiet both in their actual volume and in their general level of recognition - sounds that lack audibility (analogous to visibility). Eisuke is interested both in sounds that reside outside of our human hearing range (mostly ultrasonic sounds), and sounds that also lack "hear"-ability because of how remote they are (he studies highland gong music from Vietnam). We picked two sites in the city noted for their quietness and sonic diversity.

The first place we went was already very familiar to me - the Kamo River. When we arrived, we found ropes installed over parts of the river that were designed to deter birds from eating fish that were swimming upstream to spawn during the spring season. The ropes would vibrate with the wind and cause a really deep frequency sound that we could record with our contact mics.

Here is what one of the ropes sounded like:

Eisuke made a similar recording as well:

I also recorded some sounds from the surface of the water with my mobile listening kit.

Eisuke also recorded sounds from underneath the Kamo River with his hydrophone.

We also found a nearby pipe that captured and reverberated the sounds of the river.

Eisuke was able to stick a mic in the pipe and record some of the sounds inside.

The next day we traveled to Katsura and Kamikatsura, located near the mountains northwest of central Kyoto. There we recorded the sounds of the Hankyu Line, the Katsura River and a nearby bamboo forest.

Against the fence you can hear the roaring and rumbling of passing bikes, cars and trains.

Closer to the mountains, we visited Jizo-in Temple.

In this temple, you could hear the sounds of birds in the bamboo...

and the sound of two flowers rubbing against bamboo while swaying in the wind.

Further up we recorded the sounds of a small falls near the Katsura river. I recorded some sounds with my mobile listening kit.

Eisuke recorded similar sounds from the same river with his parabolic microphone.

He also captured the sounds of the rustling bamboo...

...and these incredibly physical sounds of large bamboo shoots cracking and snapping.

Reception

In my final week in Kyoto, we hosted a reception at Social Kitchen to present our past work and our collaboration together.

At the end of the reception we did a live performance of our field recordings.

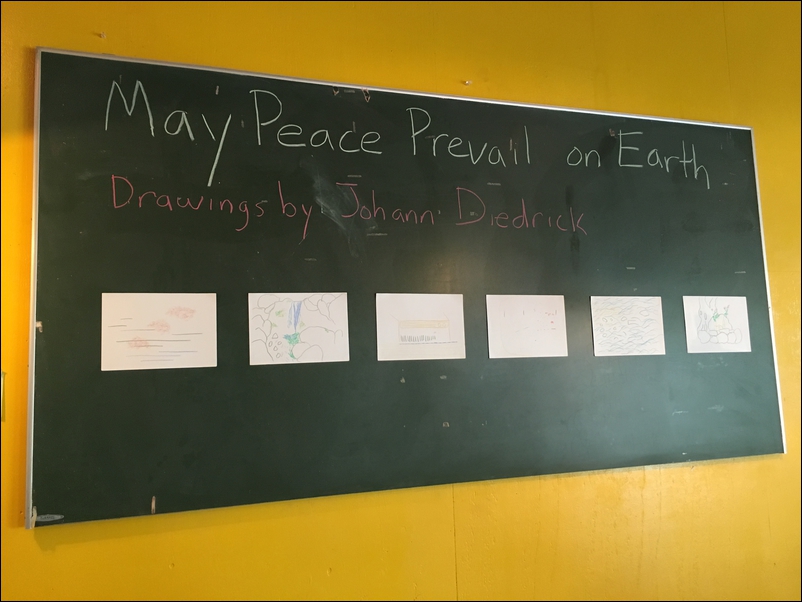

May Peace Prevail on Earth

Over the past few years, I have been documenting my explorations of weak sounds through short recordings with my mobile listening kit and photos taken with disposable cameras. That project, titled It Is Impossible To Know About Earth, So We Must Hear Her Voice In Our Own Way is still ongoing. During this residency, however, I decided to try documenting my recording situation with drawings as well. As part of the reception, I showed a selection of these drawings in a tiny exhibition titled May Peace Prevail on Earth.

Reflections

Four weeks may not sound like a lot of time for a residency, and it isn't. With that in mind, Eisuke and I designed an incredibly packed itinerary, with most of our activities happening over the course of my last two weeks.

A part of me is still deciding on whether or not it was a good idea to plan as much as I did for my time in Kyoto. On one hand, I was only going to be there for a short amount of time, so I thought it would be best to pack in as many events and activities as possible. On the other hand, I didn't have as much time to wander and explore as I wanted to. No doubt I was able to really feel like I sunk into Kyoto, but it would have been nice to have had more idle time to let my mind drift.

I also, intentionally or not, decided not to do as much material preparation for my workshops before I arrived. A lot of this was circumstantial, as I was traveling from another conference/workshop and probably couldn't have really brought all the materials I needed in the first place. Either way, one of the challenges that I set up for myself was answering the following questions:

What would it be like to be an artist in Kyoto?

Would I be able to find the materials I need to produce the kinds of work that I want?

Would I feel happy, inspired and able to live out my fullest artistic life here in this city?

I can say with confidence that I was able to pull off most of what I sent out to do during my time there.

Looking back at my time at Social Kichen, I feel like I developed more confidence in my artistic practice. I more firmly know what I like to do, and, maybe more importantly, what I don't like to do. For example, I know now that I am less interested in making works that are meant to be consumed on a screen. Instead I want to make more works that get people to stand up, move around, and interact with each other and the sounds around them. My mobile listening kits were always an extension of this desire, and the Aeolian harp workshop, which was so delightful to me, seems to be a continuation of that trajectory.

Even more so, I feel like I'm moving a bit away from sound recordings in general and more into physical sound environments that can be manipulated and played with. I'll probably still be interesting in documenting my "sonic experiences", but as my interest in drawing makes apparent, how I chose to document these experiences will constantly change and evolve.

One thing I am excited to do is improve my workshops. Having done so many now, I feel confident in facilitating them. I am already looking to improve my workshops by creating pictorial instructional guides that can be understood and enjoyed by anyone regardless of language. It would be much more time efficient and helpful if I can provide participants an instructional guide that they can go off with and use, allowing me to occasionally hop in when they need specific assistance.

One thing I am curious about working on more are self-sustained sound installations that use solar power to power speakers for amplification and natural sources of energy (wind, water) for sound activation. I am working on two new works, one for this year's Megapolis Festival and another for a group show at Little Berlin (both in Philadelphia), that have me working through these ideas and with these materials.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Asian Cultural Council for their financial and institutional support.

I would also like to thank Social Kitchen, especially Sakiko Sugawa, Makato Hamagami, Asuka Okajima, Kumi Wakao, Yuh Wakao, and Shingo Yamasaki.

Finally I would like to thank my collaborator Eisuke Yanagisawa.

Thank you Mehan Jayasuriya for helping to edit this post!